William Check, PhD

September 2016—In December 2007, American hematopathologist Tracy I. George, MD, spent a weekend in the small town of Ansbach in central Bavaria in the laboratory of Hans-Peter Horny, MD, whom she calls “the father of mast cell pathology.” Dr. Horny was at that time a privately practicing hematopathologist after having spent most of his career in academia. Plans for an international clinical trial were underway to evaluate the investigational drug midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis, a rare group of diseases for which there was no effective therapy, and Dr. Horny would be the study pathologist. Dr. George, who had been diagnosing mast cell diseases for several years, wanted to take part as well.

“There was some concern since I had not published all that much. It was very early in my career,” says Dr. George, who is currently a professor of pathology, division chief of hematopathology, and vice chair of clinical affairs at the University of New Mexico. She put her expertise on the line and traveled to Ansbach. “I had nothing to lose and everything to gain,” she says.

“[Dr. Horny] quizzed me on mast cell disease diagnosis,” Dr. George recalls. “He was incredibly nice, but it was clearly a test. I guess I passed.” Dr. George became the study pathologist for the diagnosis and evaluation of U.S. and Canada patients, while Dr. Horny, who is now a professor in the Institute of Pathology at Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich, handled those from Europe and Australia. “The easy call for study pathologist was professor Horny alone,” Dr. George says, “but I muscled my way in.”

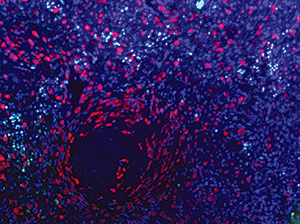

Mast cell leukemia involving spleen. Mast cells (anti-tryptase, red), proliferating cells (anti-Ki-67, green), and nuclei (DAPI, purple); strong colocalization of Ki-67 and DAPI appears white. Image acquired using Nuance spectral camera. Courtesy of Tracy George, MD, and Diane Lidke, PhD, University of New Mexico Department of Pathology.

Results from that trial, reported June 30 in the New England Journal of Medicine, were “very dramatic,” she says.

Hematologist Jason Gotlib, MD, MS, Dr. George’s colleague from her time at Stanford and the initiator and principal investigator of the midostaurin trial, tells CAP TODAY that the primary endpoint of the trial was improvement or normalization of organ damage. “Sixty percent of study subjects achieved this criterion,” says Dr. Gotlib, who is an associate professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Cancer Institute.

“Of those patients who reached that mark, 45 percent achieved a major response,” defined as resolution of damage in one or more organs. In addition, the majority of patients had a greater than 50 percent reduction in the percentage of bone marrow mast cells and tryptase levels (Gotlib J, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2530–2541).

Dr. Horny says the trial could not have been successful without the pathologists’ contribution. “The input of the pathologist is highly crucial,” he says. “In particular, it is not possible to establish a diagnosis of systemic mastocytosis and its correct subtyping clinically.”

Dr. Gotlib agrees: “Mastocytosis is a challenging disease to get a handle on.”

Dr. George first became interested in mast cell disease shortly after taking a position as associate director of the hematology laboratory at Stanford following her hematopathology fellowship there. “I’m interested in things that are difficult because I want to learn to do them better,” Dr. George says. “That’s one reason I got into hematopathology—diagnosing bone marrows and lymph nodes is challenging.” For the same reason, she focused on myeloproliferative neoplasms, working with Dr. Gotlib on many cases. “There have been incredible advances in the pathology and treatment of myeloproliferative diseases in the past decade,” Dr. George says.That interest led her to mast cell disease, which, until recently, had been considered a subtype of myeloproliferative neoplasms. “In 2016 it got its own classification,” she says. Dr. George worked with Dr. Gotlib in 2003 on a patient who had mast cell leukemia. “It is very uncommon,” she says. “That was my first one. Many pathologists have never seen one.”

Dr. Gotlib’s Stanford hematology colleague, Caroline Berube, MD, was the first to see the patient. Dr. Berube knew of Dr. Gotlib’s interest in investigational drugs for systemic mastocytosis and asked him, “Do we have anything?” At that time cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine) and interferon had been tried in small trials in mastocytosis, but they had only partial remitting activity with lack of durable follow-up.

Dr. George

Dr. Gotlib knew of midostaurin (then called PKC412), an investigational agent that was being tried in imatinib-resistant hematologic disorders. He also knew that 90 percent of cases of systemic mastocytosis were intrinsically resistant to imatinib due to the presence of the KIT D816V mutation, the genetic variant that activates mast cells and turns on constitutive cell signaling. When he petitioned Novartis to get PKC412 for compassionate use, the company declined. Dr. Gotlib then contacted Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, a researcher at Harvard who had been working with the drug and had just shown, with colleagues, that it caused significant inhibition of growth in a murine transplant model of a myeloproliferative disease caused by the imatinib-resistant FIP1L1-PDGFRA T674I mutation (Cools J, et al. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:459–469) as well as potent inhibition of a KIT D816V-transformed cell line that was also resistant to imatinib. Based on these findings, Novartis agreed to release PKC412 for compassionate use in the Stanford patient.

“The patient did remarkably well,” Dr. George says. “At the outset she had 40 percent circulating mast cells. Within days of starting treatment they dropped to zero.” Liver function abnormalities also significantly resolved (Gotlib J, et al. Blood. 2005;106:2865–2870). “When the patient came in she was at death’s door,” Dr. George says. “After treatment with midostaurin she was able to go home and resume normal life.

“That’s a dramatic story. Unfortunately, she also had an associated myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm.” While the mast cell disease improved, the MDS/MPN evolved to acute myeloid leukemia.

Even so, this result was sufficiently encouraging that Dr. Gotlib and Dr. George initiated a clinical trial of midostaurin in advanced systemic mastocytosis at Stanford and two other U.S. sites. In their early results they saw findings similar to those of their initial patient. “The main point,” she says, “was that responses were ultimately seen in 18 of 26 patients, an impressive 69 percent.” She and Dr. Gotlib presented these results at the meeting of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis in November 2008 in Budapest.

Along with the clinical data, Dr. Gotlib presented Dr. George’s images of bone marrow and blood of patients with very high numbers of mast cells being greatly reduced during treatment, and Dr. George gave a presentation on bone marrow evaluation in treated patients. “The data wowed the entire conference,” Dr. George says. “The audience appeared to be stunned by the results Dr. Gotlib presented, showing a highly effective treatment for patients with advanced systemic mastocytosis.” After Dr. Gotlib’s presentation, the audience applauded and asked numerous questions. When the session concluded, physicians and scientists gathered around them “asking for more details about what we had seen in our patients,” Dr. George says. “I can’t even begin to explain how exciting this was.”

Dr. Horny, too, recalls the audience’s response. “The reactions in Budapest in 2008 were enthusiastic!” he told CAP TODAY in an email.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management