Editor: Frederick L. Kiechle, MD, PhD

Submit your pathology-related question for reply by appropriate medical consultants. CAP TODAY will make every effort to answer all relevant questions. However, those questions that are not of general interest may not receive a reply. For your question to be considered, you must include your name and address; this information will be omitted if your question is published in CAP TODAY.

Q. Is there a place for procalcitonin testing alongside PCR testing on the BioFire system? Our facility has saved a tremendous amount of money on decreased lengths of stay by implementing a sepsis protocol that uses the typical emergency department treatment as well as lactic acid levels and PCR, which gives us a definitive response in about an hour after a blood culture turns positive. Is there any way that PCT can be seen as an enhancement to this process?

A. March 2020—It appears that this laboratory is using the BioFire blood culture identification test and is curious whether procalcitonin would add value. If so, my answer would be a definitive maybe. There are at least two areas in which PCT might add value. The first is related to typical ED treatment, as mentioned. In many places, this treatment would be an initial dose of broad-spectrum antibiotics while the blood culture/BioFire results are pending. With appropriate turnaround time and clinician buy-in, PCT results might help reduce this initial treatment. The caveat is that while the literature shows strong negative predictive value for PCT, most clinicians with whom I have dealt are hesitant to withhold that first dose based on PCT. There is a strong desire to do something while awaiting the culture/BioFire result.Still, getting that initial PCT would be important for subsequent measurements and dose de-escalation. The BioFire system is not going to cover all antimicrobial resistance mechanisms. It hits the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase but doesn’t cover imipenemase, New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase, or oxacillinases, for instance, with regard to carbapenemases. In addition, these PCR assays will struggle with novel variants that are only detectable phenotypically (a small percent but still a consideration). These challenges mean that PCT could still have a role in guiding antimicrobial stewardship.

All that said, adoption and trust of the BioFire results are much easier to achieve than adoption and trust of PCT, in my experience and opinion. It would take substantial buy-in and trust from your clinical colleagues to make sure the expense of PCT leads to improved patient outcomes.

Joshua Hayden, PhD, DABCC

Chief of Chemistry

Norton Healthcare

Louisville, Ky.

For nonrespiratory infection molecular testing, PCT (with other clinical parameters) may help improve pretest probability—that is, patients who would benefit from additional testing. An example is the new prediction rule by investigators at the University of California, Davis, for febrile infants (Kuppermann N, et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173[4]:342–351). The rule included PCT and other variables (urinalysis and absolute neutrophil count) and can rule out more serious issues, such as meningitis, and perhaps make it possible to avoid a lumbar puncture (and not require use of a molecular meningitis panel). In the end, as PCR panels expand in terms of detectable pathogens and flexibility, and perhaps with the adoption of other novel technologies beyond PCR, PCT can help optimize utilization and add to the predictive power of these tests. On our end, we’ve seen PCT-negative results (along with other clinical factors like a normal lactate, for example) help reduce unnecessary cultures and antimicrobial therapy as reported by other studies. Integrating PCT with other workflows that include molecular diagnostics is the next logical step.

Nam K. Tran, PhD, HCLD(ABB)

Associate Clinical Professor

Director of Clinical Chemistry,

Special Chemistry and Toxicology, Point-of-Care Testing, and SARC

Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

UC Davis School of Medicine, Davis, Calif.

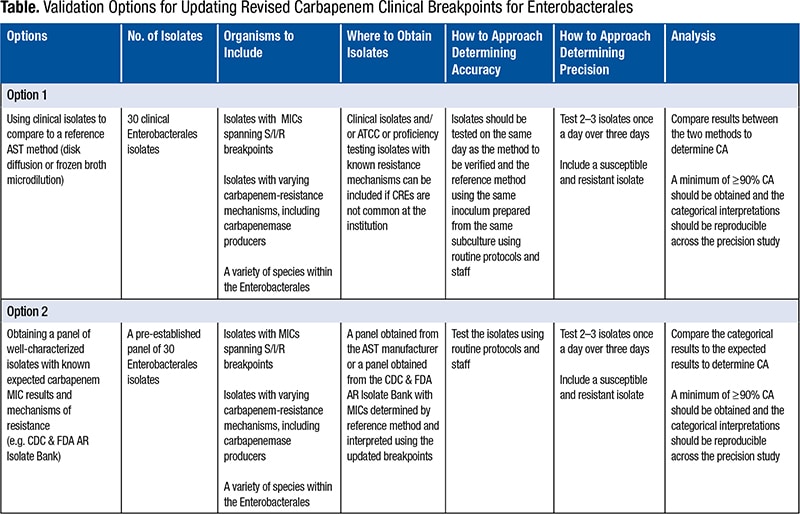

Q. We are looking into validation methods for lower breakpoints for carbapenems. The CDC has banks of organisms available to run on our Vitek 2 (BioMérieux). Are there guidelines on which organisms to include and how many times to test?

A. This question is particularly pertinent because the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute updated more clinical breakpoints in 2019 than it has in any single year since 2010.1 Keeping up to date with antimicrobial susceptibility test breakpoints is a challenging but critically important task for the clinical laboratory that impacts the quality of patient care and patient safety.Many laboratories struggle with the breakpoint validation process. In particular, there is uncertainty as to why a validation study must be performed at all since the analytical output—that is, the minimal inhibitory concentration—is the same, and only the interpretation is changed when implementing a new breakpoint. However, it is useful to reflect on the performance characteristics required by the FDA for AST system clearance. These include essential agreement (MIC agreement within ±1 doubling dilution) and categorical agreement (susceptible [S], intermediate [I], and resistant [R] interpretation agreement with a reference method). Systems may be tweaked by the manufacturer to ensure that the performance around a given breakpoint is ideal and both factors can be met. This tweaking may result in unacceptable performance at lower or higher MICs not bracketing the breakpoints. When the breakpoint is changed, the adjustments made thereafter may no longer be appropriate, and the FDA categorical agreement requirements may not be met. Another reason labs should validate the updated breakpoints is that the bacteria may have changed, due to changing and evolving resistance mechanisms, between the time the labs’ commercial systems were first FDA cleared and the time breakpoints were updated by the CLSI and/or FDA. For example, systems that are applying outdated carbapenem breakpoints have not been updated since 2009—a time when CREs were rare in the U.S. Therefore, laboratories should want to ensure these systems perform as well as they did when such resistance mechanisms were rare. In both cases, the laboratory should be aware of how the test system performs with the new breakpoints.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management