Karen Lusky

January 2019—Pathologists who aren’t microbiologists can provide a diagnosis of parasitic disease if they take into account parasite life cycles and tissue tropisms. Julie A. Ribes, MD, PhD, made that key point in cases she presented in her CAP18 session, “Update on Invasive Parasitic Infections for Surgical Pathologists.” Dr. Ribes added learning material to most of the cases, she said, but the cases come from parasites she has seen and known in her own professional life.

“Tropism is the organism’s predilection to home in on specific tissues,” Dr. Ribes, director of clinical microbiology at UK HealthCare in Lexington, Ky., told CAP TODAY in a recent interview. “We can predict potentially what organism is present there by looking at what tissue they have decided to take up residence in.” In lung disease, for example, “you know there are relatively few organisms that are going to have any type of transit time through the lung.” The pathologist is therefore going to focus on those organisms likely to pass through the lung or to localize there indefinitely. “Once you have in mind what organisms are likely to be in a particular tissue,” Dr. Ribes said, “you can then correlate with the parasitic structures identified to home in on a definitive diagnosis.”

“Tropism is the organism’s predilection to home in on specific tissues,” Dr. Ribes, director of clinical microbiology at UK HealthCare in Lexington, Ky., told CAP TODAY in a recent interview. “We can predict potentially what organism is present there by looking at what tissue they have decided to take up residence in.” In lung disease, for example, “you know there are relatively few organisms that are going to have any type of transit time through the lung.” The pathologist is therefore going to focus on those organisms likely to pass through the lung or to localize there indefinitely. “Once you have in mind what organisms are likely to be in a particular tissue,” Dr. Ribes said, “you can then correlate with the parasitic structures identified to home in on a definitive diagnosis.”

In her talk, Dr. Ribes provided other takeaways from her cases: Measure up, both worms and eggs. Formulate a differential based on the tissue location and stages of the parasite seen. Not all parasitic infections are accompanied by eosinophilia. Being aware of a parasite’s life cycle can be helpful. “Many of these organisms have relatively complex life cycles, so the particular stage that the human can actually serve as the host is going to be restricted,” she explains.

Dr. Ribes presented the case of a 64-year-old Vietnamese patient who had lived in the Commonwealth of Kentucky for decades. (The two “buzzwords,” she hinted, are Vietnamese and the Commonwealth of Kentucky.) The patient had undergone a bone marrow transplant for non-Hodgkin lymphoma and was taking prednisone and CellCept to support the transplant. After a prednisone taper, he was evaluated for weakness and diarrhea. “An endoscopic biopsy of the patient’s duodenum was taken when an ulcerative lesion was identified during the endoscopic workup,” Dr. Ribes said.

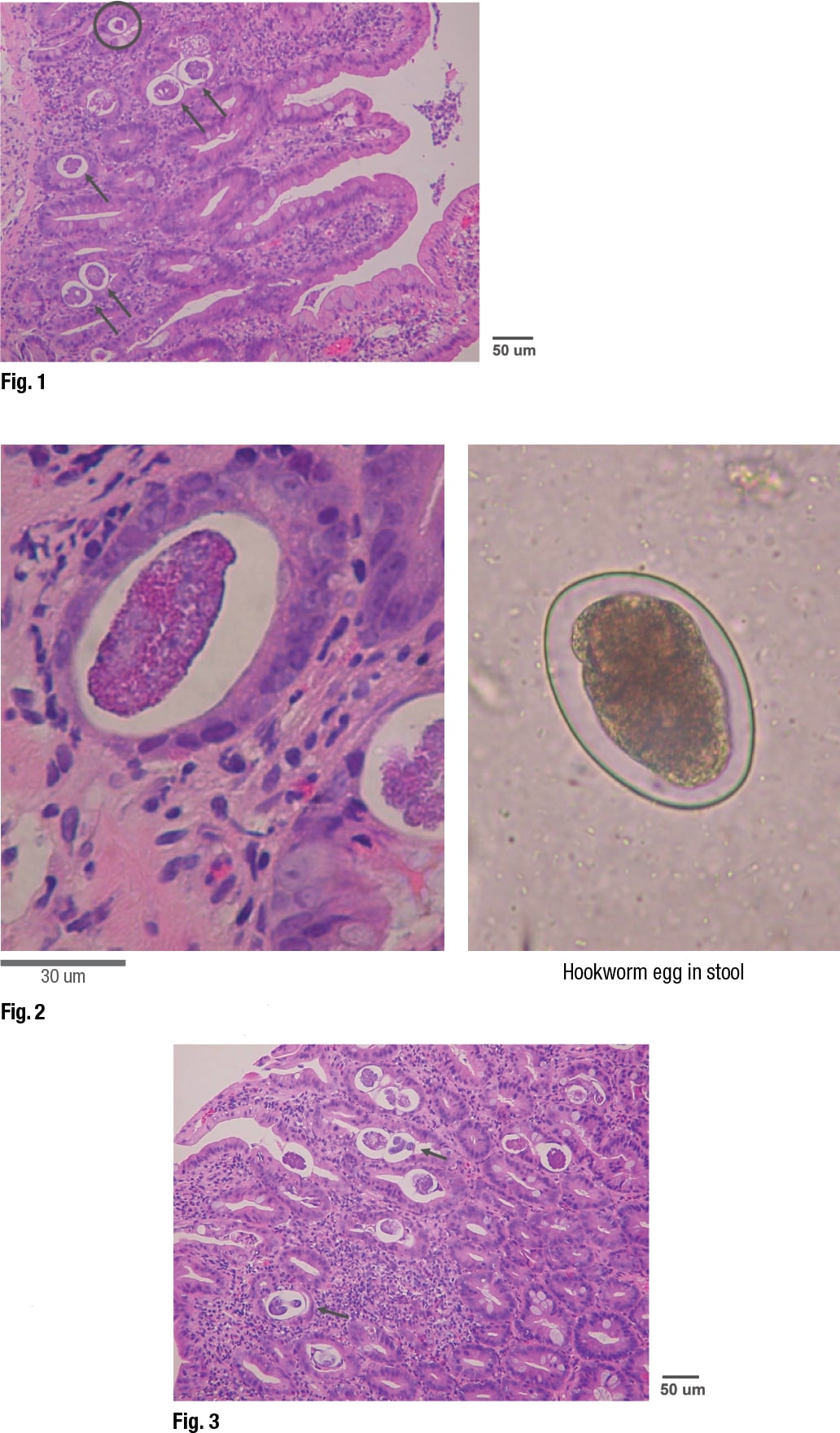

The biopsy specimen revealed “large, thin worms at 10× hanging out in the mucosal of the crypts.” In more slices through the collected tissue, they could see other structures at 50×. Those resembled “large owl-eye-like inclusions, again, retained within the bowel wall,” Dr. Ribes said. In examining further, these structures varied considerably in size. Most of the interior components were “relatively amorphous.”

Fig. 4. Strongyloidiasis: stages found in human tissues and fluids—adult worms, eggs, larvae (filariform in tissues; rhabditiform in stool). Source: CDC.

Showing an image of the specimen, Dr. Ribes pointed out that the circled structure at the top is “a very different size distribution than the rest of them.” (Fig. 1). These represented slices through eggs at different levels, giving the impression they varied in size. “It’s not that we have a huge variation in size in these structures, but that we just cut in a different place.” The larger ones are slices in the middle, and the smaller ones represent slices at the tapered ends of the eggs.

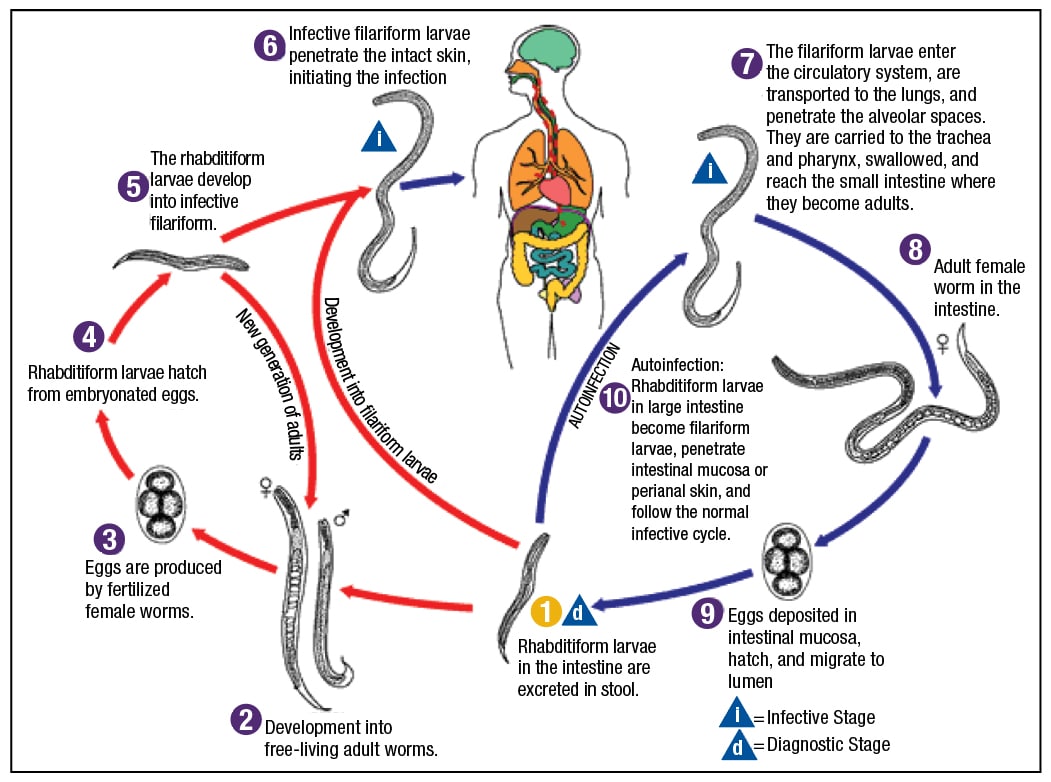

An image of another slice from the specimen displayed a “haloed structure” that Dr. Ribes dubbed “egg in tissue” on the left (Fig. 2). It was slightly larger than the image on the right, which is a hookworm egg, as it would be seen in stool. (The hookworm wasn’t from the patient.) The hookworm egg interior contents are “globular in formation,” she said, “so this is an unembryonated egg.” By contrast, the “egg in tissue” appears to have “lost the globular component and is heading toward becoming a larva.”

First of two parts. Next month: Schistosomiasis, Naegleria fowleri, maggots

In looking at the specimen further, they could see that some of the eggs were completely embryonated. “We have actual larvae that are mature and ready to erupt from these eggs. These eggs are going through their full maturation and then hatching in situ without being shed in the stool. So unlike that hookworm egg that we saw before, we are not expecting to see these eggs in a stool specimen.” (Fig. 3).

“This is strongyloidiasis,” Dr. Ribes said, noting the man was from Vietnam, “a perfect place” to get strongyloidiasis. And for decades, he has been in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. “Another perfect place to pick up strongyloidiasis. It is our Commonwealth worm.”

“This is strongyloidiasis,” Dr. Ribes said, noting the man was from Vietnam, “a perfect place” to get strongyloidiasis. And for decades, he has been in the Commonwealth of Kentucky. “Another perfect place to pick up strongyloidiasis. It is our Commonwealth worm.”

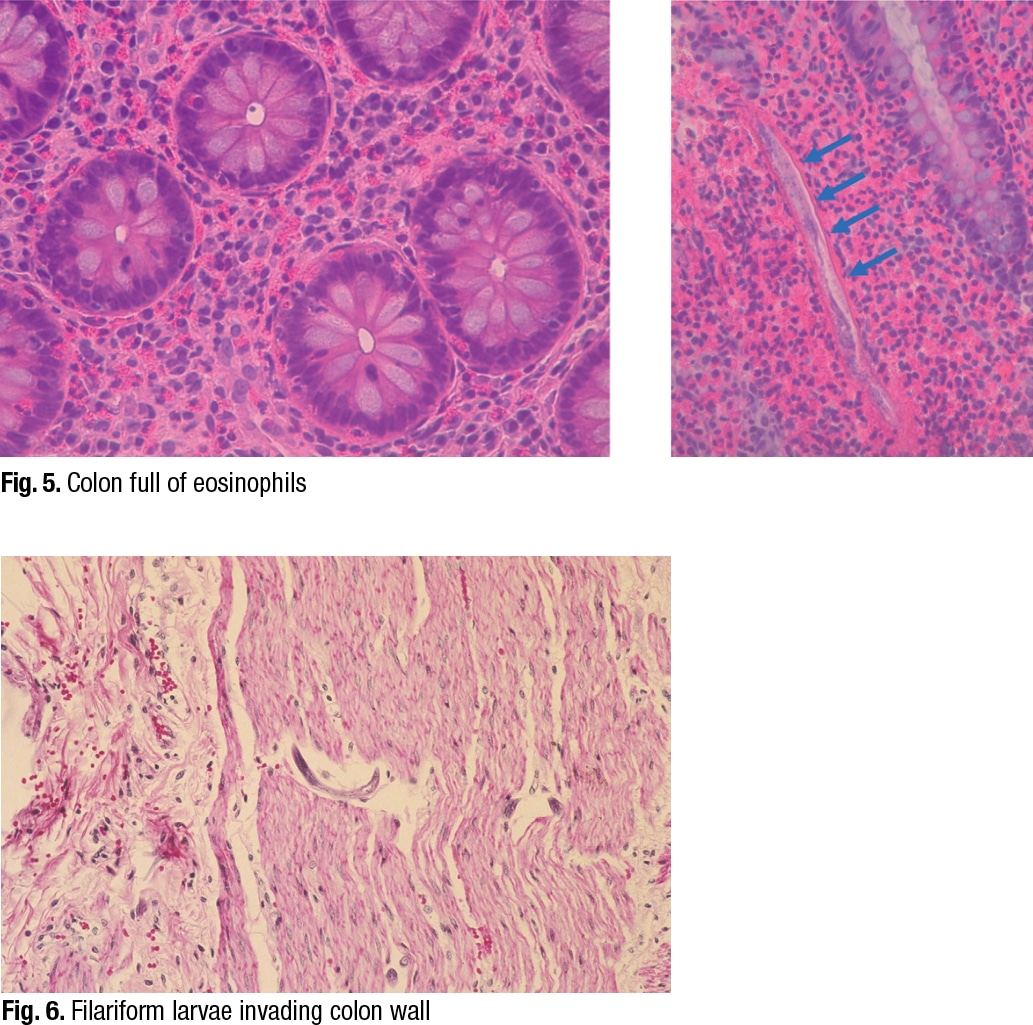

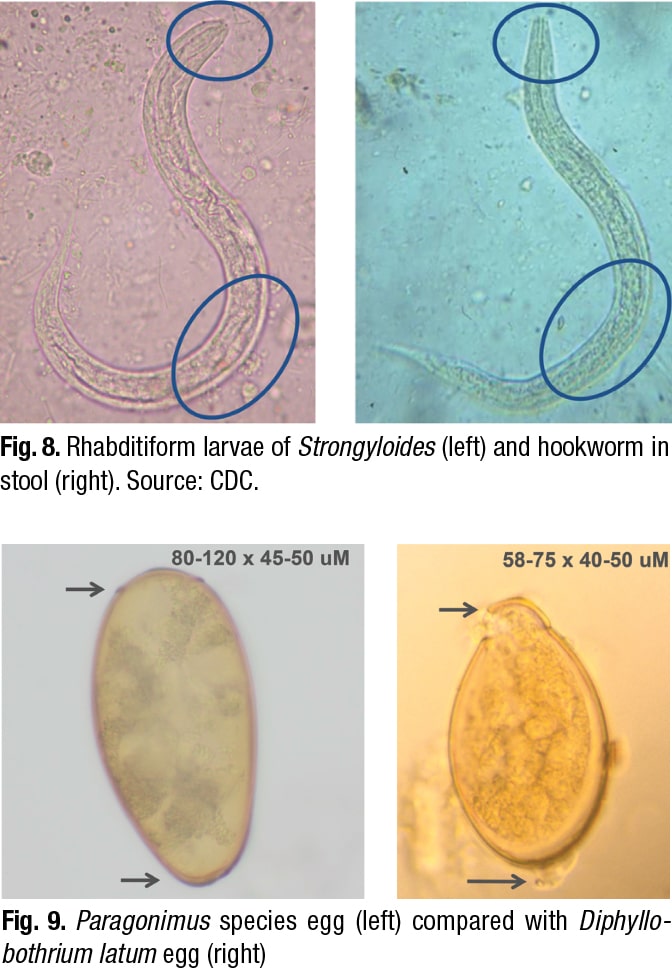

Dr. Ribes pointed out that Strongyloides has two different types of larvae (Fig. 4). The cycle begins with “free-living adult worms mating in the environment, producing eggs that produce rhabditiform larvae.” These can mature back into adults and continue that life cycle in the environment.

“If, however, they go on to mature into a filariform, free-living infective stage, they are prepared to become the parasite for an unsuspecting human walking barefoot in the dew-laden grass of eastern Kentucky,” she said. The filariform larvae will “percutaneously invade” and obtain access to the venous system. “They will be impacted into the patient’s lung, be coughed up, swallowed down, and then will take up residence in the duodenum, where the adult worms will then go ahead and produce more eggs.”

Only the females are invasive. “There is no mating that occurs in the host.” Reproduction occurs by parthenogenesis, Dr. Ribes said, which is the maturation of an unfertilized egg.

The patient from Vietnam is likely to have had a chronic infection from Vietnam, Dr. Ribes said. “When we throw steroids at this infection, what we see is that rhabditiform larvae are stimulated to mature directly into the filariform larvae, which is then capable of directly penetrating the skin or bowel wall.”

In the setting of high-dose steroids, or even low-dose, “these guys will enhance that hyperinfection syndrome, and we can see infections with massive numbers of organism that will be produced.” The filariform larvae “may drag with flora from the bowel as they invade tissue and vasculature,” she said, “and you can see sepsis and fungemia, or meningitis.” The filariform larvae can be found in various tissues.

The Vietnamese patient from Kentucky had strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. “When we looked at this stool, it was full of rhabditiform larvae,” Dr. Ribes said. “They began treating him, and the next day you could actually see these adult worms being shed in the stool,” along with rhabditiform and filariform larvae. “He was shedding huge numbers of these in his stool over the next several days.”

The Vietnamese patient from Kentucky had strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. “When we looked at this stool, it was full of rhabditiform larvae,” Dr. Ribes said. “They began treating him, and the next day you could actually see these adult worms being shed in the stool,” along with rhabditiform and filariform larvae. “He was shedding huge numbers of these in his stool over the next several days.”

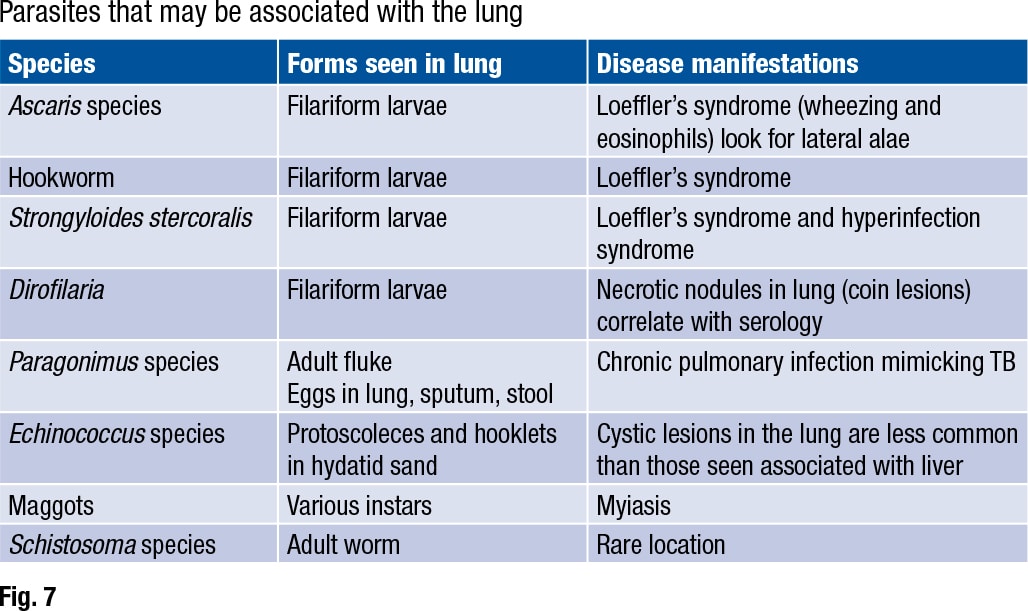

In reviewing their past cases of strongyloidiasis, Dr. Ribes and colleagues found that eosinophilia was probably present in about 20 to 25 percent of them, and it was intermittent. “Depending on the patient, eosinophilia varies greatly,” she said, showing an image of eosinophils in the colon (Fig. 5). On the right side of the image is another characteristic feature. “As the rhabditiform larvae are being stimulated by steroids to mature into filariform free-living invasive forms, we can see that they may begin piercing through the bowel wall and be identifiable as what I refer to as speckled bands.”

She pointed to a different case (Fig. 6). “In this case there’s no eosinophilia,” she said, “but notice speckled bands. We have a hyperinfection syndrome even here, but without all that eosinophilia. So the eosinophilia may be helpful when present, but not necessarily helpful if not present, but certainly be looking for the speckled bands.”

The Strongyloides life cycle includes a migratory phase through the lung (Fig. 7). Ascaris, hookworm, and Strongyloides stercoralis are all associated with “a migratory phase through the lung, often stimulating a brisk eosinophilia, wheezing, and other respiratory symptoms,” Dr. Ribes said. This is called Loeffler’s syndrome. “Filariform larvae may be seen in bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum for all these worms, so correlate with O&P on stool for a definitive identification.”

The Strongyloides life cycle includes a migratory phase through the lung (Fig. 7). Ascaris, hookworm, and Strongyloides stercoralis are all associated with “a migratory phase through the lung, often stimulating a brisk eosinophilia, wheezing, and other respiratory symptoms,” Dr. Ribes said. This is called Loeffler’s syndrome. “Filariform larvae may be seen in bronchoalveolar lavage and sputum for all these worms, so correlate with O&P on stool for a definitive identification.”

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management