David Wild

September 2018—The advantages of moving from stool culture to a molecular platform are many: faster time to results, more accurate pathogen identification, a savings of space and staff time. For Jose Alexander, MD, D(ABMM), SM, MB(ASCP), and colleagues at Florida Hospital Orlando, another plus is being able to adhere to the Infectious Diseases Society of America guideline suggestion that labs use a diagnostic approach that can distinguish O157 from non-O157 E. coli and Shiga toxin 1 from Shiga toxin 2 E. coli.

Dr. Alexander, a medical and public health microbiologist and the hospital’s director of clinical microbiology, shared the story, in a webinar this spring and in a recent interview, of how his laboratory made the decision to switch to PCR.

“Moving from stool culture to a molecular platform seems to be the next big step for many laboratories, not only for the improvement of the technique for detection of pathogens and the benefits to the patient but also for the benefits to the laboratory itself,” he said in the webinar, which was hosted by CAP TODAY and made possible by a special educational grant from Luminex.

One of the first things Dr. Alexander and his colleagues at Florida Hospital Orlando considered when weighing a switch was the department’s stool culture volume and the cost implications. The Florida Hospital system has a 24/7 central microbiology department staffed by 42 full-time medical technologists and technicians for its 2,400 beds across seven hospitals and multiple long-term and nursing home facilities. By 2017, when the department made its case for molecular testing in place of culture, 780,000 tests were performed in the department, of which 7,200 were stool cultures.

“One of the most important steps in making the case for a switch to PCR and selecting the right panel for us was to document the types of organisms we had been screening for through stool cultures,” Dr. Alexander said.

In 2016, the microbiology department cultured 6,800 stool samples, two-thirds of which were for outpatients, and found the most prevalent pathogen was Salmonella spp., with 163 cases, followed by 82 cases of Campylobacter spp. and 28 cases of Shigella spp. Other less common pathogens isolated included four cases of Escherichia coli O157, two cases of Yersinia enterocolitica, four cases of Plesiomonas shigelloides, five cases of Shiga toxin 1-producing E. coli, and two cases of Shiga toxin 2-producing E. coli.

Although this pathogen distribution matched what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network reported in recent years, Dr. Alexander said, “we still felt like stool cultures were not actually detecting the amount of organisms that are circulating in our population.”

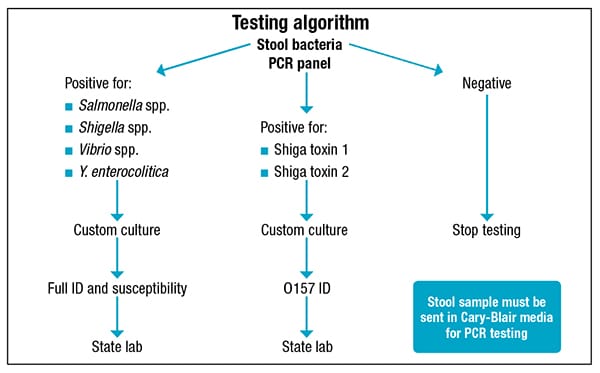

Testing by PCR would mean redistributing the benches and staff, a 24-hour turnaround time, greater sensitivity, and improved in-house viral detection. “We can also have more space in the ambient incubator,” he said. It also meant having to purchase less special media and being able to screen routinely for Vibrio and Yersinia, which are now a separate order. “But the most important advantage is we can screen for Shiga toxin genes for detecting non-O157 and also non-toxin-producing Shiga toxin E. coli.” Routine culture will not detect many non-O157 or low-level producing or non-producing Shiga toxin E. coli.

Testing by PCR would mean redistributing the benches and staff, a 24-hour turnaround time, greater sensitivity, and improved in-house viral detection. “We can also have more space in the ambient incubator,” he said. It also meant having to purchase less special media and being able to screen routinely for Vibrio and Yersinia, which are now a separate order. “But the most important advantage is we can screen for Shiga toxin genes for detecting non-O157 and also non-toxin-producing Shiga toxin E. coli.” Routine culture will not detect many non-O157 or low-level producing or non-producing Shiga toxin E. coli.

Switching to PCR meant, too, that Florida Hospital would fall in line with the 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea, which encourage use of “culture-independent methods” of stool testing for possible bacterial or parasitic causes as well as possible C. difficile infection.

When Dr. Alexander and colleagues calculated the cost of a culture, including the special media, GN broth, Shiga toxin EIA, and Vitek ID cards, they “got a big surprise,” finding that a single stool culture cost nearly $28. When they factored in the cost of operator time—five minutes for setup and 30 minutes of hands-on time per culture over five days—the cost rose to almost $53 on average.

“With PCR, the hands-on time is down from 30 minutes to less than five minutes per sample, and we can remove a bench,” he said.

Dr. Alexander and his colleagues decided they would transition to PCR stool testing and deliberated between two platforms: the BioFire FilmArray and the Luminex Verigene Enteric Pathogens test. They chose the latter, in part because the platform was already in-house.“One of the advantages of the Verigene for us was that it included many of the targets indicated in the IDSA guidelines and we could create custom bacterial or viral panels,” Dr. Alexander said. “The BioFire has multiple other targets and has a very interesting group of targets for parasites, but it also includes C. difficile, which we were already testing for using a separate molecular platform and a completely different protocol. Keeping C. difficile separate made implementation a bit easier.”

He explains: “The IDSA C. difficile guideline came out at a good moment for us.” It says when there are no pre-agreed institutional criteria for patient stool submission, the “double step” approach is best—GDH plus toxin, GDH plus toxin arbitrated by nucleic acid amplification testing, or NAAT plus toxin. “We use GDH and toxin, and discrepancies are solved using a PCR platform,” one that is different from Verigene. “And this is something we already implement and we continue to be performing in that direction.”

While the Verigene test does not identify parasites, the clinical manifestation and epidemiological background of parasitic infections is “quite different from bacterial and viral causes,” he said. With no parasite panel to include, he added, “we are going to deal with the parasite in a completely different scenario.”

They asked themselves whether they needed a panel to detect Plesiomonas shigelloides and Aeromonas—which the Verigene test does not include—and decided they did not, since the health system isolated only two P. shigelloides and no Aeromonas in 2016 using stool culture. “Although those two organisms were not a concern for us and not necessary to include in a molecular panel, we did decide to offer a custom stool culture for these organisms in case the microbiology department wanted to test for these,” Dr. Alexander said.

Once they determined the Verigene system best suited their needs for enteric pathogen testing, Dr. Alexander and his colleagues validated the sensitivity and specificity of the test using 58 frozen stool samples they had previously cultured. Ten were known negative and 48 were known positive and included Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Vibrio, Yersinia enterocolitica, Shiga toxin 1 and 2 E. coli, as well as rotavirus and norovirus. Dr. Alexander and his team found the panel was 100 percent sensitive and 100 percent specific: “All the targets were detected as suspected.”

“Worth noting is that the custom Verigene multiplex panel we built includes nine different targets, but the samples we used only tested positive for the single target we tested for,” Dr. Alexander said. “So that means every time you run the sample, you have one positive target detected but you also have eight negative targets. This is something to consider in your validation protocol.”

They also tested for reproducibility by running at least five samples twice by the same operator and for precision by running at least five samples twice by two different operators. “One hundred percent reproducibility and precision were obtained,” he says.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management