Desiree Marshall, MD; Dhruba J. SenGupta, PhD; Daniel R. Hoogestraat, MB(ASCP); Karen Stephens, PhD; Brad T. Cookson, MD, PhD; Cecilia C.S. Yeung, MD

February 2013—CAP TODAY and the Association for Molecular Pathology have teamed up to bring molecular case reports to CAP TODAY readers, starting this month. AMP members will write the reports using clinical cases from their own practices that show molecular testing’s important role in diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and more. We aim to publish a few a year. The first such report comes from the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle. (If you would like to submit a case report, please e-mail the AMP at amp@amp.org. For more information about the AMP, visit www.amp.org.)

February 2013—CAP TODAY and the Association for Molecular Pathology have teamed up to bring molecular case reports to CAP TODAY readers, starting this month. AMP members will write the reports using clinical cases from their own practices that show molecular testing’s important role in diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and more. We aim to publish a few a year. The first such report comes from the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle. (If you would like to submit a case report, please e-mail the AMP at amp@amp.org. For more information about the AMP, visit www.amp.org.)

Abstract

Zygomycoses are morbid and often fatal diseases. We report a case of unexpected primary gastrointestinal zygomycosis presenting as small bowel obstruction with a palpable abdominal mass in a marrow transplant patient. This patient incurred a rapidly fatal hospital course, and subsequent autopsy findings showed ambiguous histologic features in the fungus requiring molecular identification. The case demonstrates the importance of recognizing zygomycosis as a rapidly fatal process in an immunocompromised patient despite the unusual presentation. It also highlights the utility of gene sequencing in a postmortem setting for speciation of fungal organisms, both for providing a definitive diagnosis and additional information for infection control.

Introduction

Zygomycosis is the third most common invasive fungal infection, representing 8.3 to 13 percent of fungal infections at autopsy in hematology patients.1 Mucorales fungi, which cause the majority of human disease, are an order of Zygomycetes and include the genera Rhizopus and Mucor. They are ubiquitous and cause acute angioinvasive infections in immunocompromised patients.1 Many institutions have shown increased frequency of zygomycosis attributed to increased use of immunosuppressive drugs and antifungal therapy lacking activity against Mucorales (for example, voraconazole).1,2 Populations at risk include patients with hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, prolonged neutropenia, solid organ transplant, iron overload/deferoxamine therapy, major trauma, prolonged use of corticosteroids, illicit intravenous drug use, neonatal prematurity, and malnourishment.2

We report a case of unexpected, rapidly fatal primary gastrointestinal zygomycosis presenting as small bowel obstruction with a palpable abdominal mass in a marrow transplant patient. Subsequent autopsy findings required molecular testing by gene sequencing to identify the organism. We report this case for the purpose of recognizing a rapidly fatal process in an immunocompromised patient and to describe the utility of molecular methods in speciation of fungal organisms in a postmortem setting.

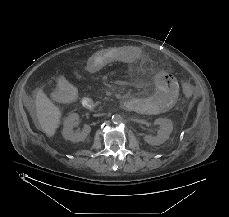

Fig. 1. Abdominal CT showing small bowel with minimal residual lumen and mucosal thickening surrounded by extensive inflammatory mesenteric fat stranding.

Patient case

A 67-year-old man with transformed diffuse large B cell lymphoma from follicular lymphoma was admitted with severe mucositis and nausea/vomiting four days following autologous peripheral stem cell transplant. His past medical history was significant for insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes mellitus complicated by renal insufficiency, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and colonization by vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Social and family history included distant work on nuclear submarines and a sister in remission from follicular lymphoma. Upon admission, he was on a prophylactic regimen of levofloxacin, fluconazole, and acyclovir. He developed neutropenic fever on hospital day two with absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of 0/mm3, and levofloxacin was changed to ceftazidime. That evening he had an episode of bilious vomiting, suspicious for small bowel obstruction. Two days later, he demonstrated neutrophil engraftment with ANC of 800/mm3, but also developed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response and underwent cardioversion. Abdominal CT revealed small bowel dilation and wall thickening with extensive mesenteric fat stranding and enlarged retroperitoneal lymph nodes. The differential diagnosis included ischemia secondary to embolic event, infection, recurrent lymphoma, chemotherapy-related toxicity, graft-versus-host disease, or vasculitis.

His multiple comorbidities made him a poor surgical candidate, and conservative management with the addition of metronidazole was initiated on hospital day four. Although he showed initial improvement, his abdominal symptoms progressively worsened. He had a heme-positive bowel movement on hospital day 14 with stool culture negative for Clostridium difficile and Norovirus; planned additional studies were not performed due to insufficient material. Repeat abdominal CT on hospital day 15 showed progression of the abdominal process (Fig. 1). The next day he had blood per NG tube, left upper quadrant ecchymosis, increased abdominal distension, and an underlying palpable mass. He continued to decompensate until hospital day 18 when he died after unsuccessful resuscitative efforts for bradycardia, acute hypotension, and acidosis.

Fig. 2. Gross photo of the annular abdominal lesion after the abdomen is opened to reveal the underlying omentum with hemorrhage and pink discoloration. The pink indurated area on the abdominal wall corresponds to the superficial cutaneous ecchymosis.

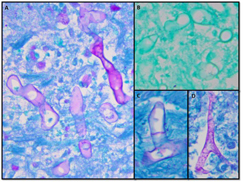

Autopsy revealed a large, complex pseudocavitary lesion formed by necrotic omentum encasing several necrotic loops of small bowel with partial entrapment of the transverse colon and two large necrotic abscess cavities in the mesentery and below the stomach. A definite perforation was not identified by gross examination. A large annular, hemorrhagic, necrotic lesion corresponded to the superficial ecchymosis on the left upper to mid quadrant abdominal skin (Fig. 2). Microscopic examination of involved tissues revealed extensive infiltration by PAS-positive, GMS-negative fungal organisms with prominent angiotropism. Some fungal forms showed Zygomycetes morphology with aseptate, ribbon-like hyphae of variable width (Fig. 3). However, some hyphae showed features not typically associated with Zygomycetes, including septa formation, narrower hyphae, and 45-degree angle branching (Fig. 3). Postmortem viral, bacterial, and fungal cultures from the omentum, brain, spleen, liver, kidney, right and left lungs, peripancreatic necrosis, and retro-gastric abscess revealed no evidence of disseminated fungal infection; however, the lungs, omentum, kidney, liver, and brain grew Enterococcus species. Extensive sampling of the tissues showed no lymphoma.

Fig. 3. Fungal histology from the pseudocavitary lesion in the abdomen showing extensive infiltration of the tissues by fungal hyphae. A) PAS-stained section showing classic ribbon-like, aseptate hyphae of variable width. B) GMS-stained section showing lack of silver reactivity in the fungal hypha. C) PAS-stained section showing clear septa formation. D) PAS-stained section showing near 45-degree angle branching.

Due to ambiguous fungal morphology, PCR analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue from the peripancreatic necrosis and retro-gastric abscess was performed with methods reported previously.3 PCR products were separated by electrophoresis using a one percent agarose gel. PCR using primers directed against internal transcribed spacer (ITS1) yielded a product that was subjected to bidirectional sequencing and contig assembly. Assembled sequence was submitted to GenBank Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search. The query sequence matched 100 percent over 312 base pairs to Rhizopus microsporus (GenBank accession No. DQ119009) and Rhizopus azygosporus (GenBank accession No. DQ119008) sequences (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Zygomycoses are classified into six major clinical forms, including rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, disseminated, and uncommon presentations. Gastrointestinal zygomycosis is uncommon, with only 25 percent of cases being diagnosed premortem because of its nonspecific presentation. This leads to frequent delay in diagnosis and a mortality rate of 85 percent.2 The stomach is most commonly involved, often with gastric perforation, followed by the ileum and cecum with presentation involving an appendiceal, cecal, or ileal mass.2

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management