Karen Lusky

March 2017—Keep eyes wide open to everything and describe everything because there might be a number of different factors playing into a patient’s disease. That was the reminder Robert M. Najarian, MD, opened with last fall in his CAP16 presentation on common patterns of liver injury.

Dr. Najarian, a consultant in gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, and pancreatic pathology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, began with a case to illustrate.

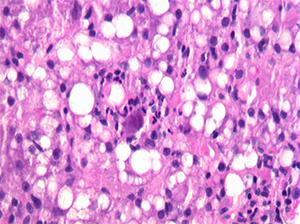

Fig. 1

A hepatologist wanted to know if a jaundiced patient was still imbibing alcohol. The patient had a history of past alcohol abuse and was transplanted for alcoholic steatohepatitis. In an image he showed of the biopsy of the woman’s transplanted liver (Fig. 1), Dr. Najarian noted there was clearly an active steatohepatitis present. But then he described a feature visible in the center of the image: “This very large sort of smudgy-looking cell with some eosinophilic—what look like—inclusions.”

The biopsy really had two stories to tell, Dr. Najarian said. One was alcohol use. The patient had not been following up with her physicians but returned for care after her skin became yellow after heavy drinking at home. And she had cytomegalovirus infection, commonly seen in post-transplant patients.

“The whole purpose of showing that case to everyone was to highlight that we sometimes focus on the most obvious histologic finding and run with it and blame the patient’s presentation on a single entity,” Dr. Najarian tells CAP TODAY.

In his presentation, Dr. Najarian reviewed the common patterns of liver injury seen in medical liver biopsies, including the steatohepatitic or toxic-metabolic pattern, commonly associated with alcohol, excessive weight and other metabolic syndrome risk factors, and other inherited and acquired metabolic diseases. Some patterns are specific for particular disease entities. “These usually fall into the realm of certain viruses that you can clearly identify on H&E-stained slides,” he said. Other common patterns are a biliary or cholestatic pattern, with bile duct obstruction as the “classic example,” a vascular pattern of injury, and an active or chronic hepatitic pattern. The latter is frequently associated with, among other things, autoimmune hepatitis and viral hepatitides.

Dr. Najarian focused on what he called the “dreaded visitors” that pathologists don’t want to see on their microscope stage: eosinophils, plasma cells, and steatotic hepatocytes in liver biopsies. “When we see eosinophils, we wonder how specific is this for any one particular entity,” he said. “Am I dealing with a drug reaction, which, after all, is supposed to have eosinophils? Am I dealing with a parasitic infection, which would be very unusual? Or is this just something else where the eosinophils are coming along for the ride?” Where, he asked, can the pathologist find clarity?

Are pathologists always dealing with an autoimmune hepatitis or an immune-mediated type of injury when they see plasma cells? “And what other laboratory data or information should I be looking for to help provide clarity in this instance?”

Cases in which steatosis is a concern are less of an issue in terms of identifying them because it’s fairly easy to see, he said. More important, in his view, are specificity and knowing what questions to ask the clinician and the patient.

Dr. Najarian presented case studies and other material on each of the microscopic visitors, starting with eosinophils. He described the first example as “a strange case of eosinophils causing havoc.” It was “an extremely uncommon pattern,” Dr. Najarian tells CAP TODAY, unlike anything he’d ever seen before.

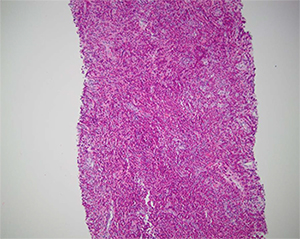

Fig. 2

The clinician was suspicious that a 54-year-old male patient had a neoplastic process. The patient had multiple mass-forming lesions in the liver but no history of a previous cancer. Dr. Najarian believed at the outset that it was a tumor of unknown origin and thought, “Let’s get the immunostains ready for that purpose.” The patient had a 100-pack per year smoking history, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. He had no recent foreign travel or history of infection, sick contacts, or unusual food consumption.

However, when Dr. Najarian initially looked at the biopsy under the microscope, he was taken aback. “It was actually the most splendid example of eosinophilia in the liver I have ever seen. And I said, ‘My God, there’s nothing but the eosinophils here,’” he recounted in his talk, showing an image of the biopsy. There weren’t any neoplastic cells except potentially neoplastic eosinophils, but all of the eosinophils were of normal morphology (Fig. 2).

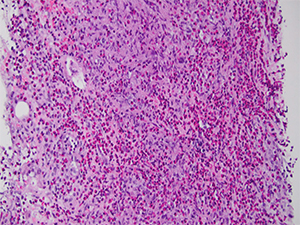

Dr. Najarian said that he ultimately looked in other fields and observed a background of pale staining cells that had amphophilic cytoplasm and spindle-shaped nuclei, which he showed in a separate image. He didn’t see any parasite eggs, microorganisms, or indication of an organizing abscess. “Certainly, eosinophils made me think of ruling out infection,” he said, “but generally when [there’s] an infection and a consequential abscess, you typically expect to see some neutrophils, or in the organizing phase, you’d see some form of granulation tissue and not really one isolated cell population, the eosinophils, standing out. They tended to be in the background of other cases I had seen” (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Dr. Najarian said he did a mast cell tryptase stain, thinking, “Could those spindle cells be mast cells because we know they can look like anything, and anywhere there are mast cells there are commonly eosinophils because of a common group of cytokines that recruits them.” His short list of possible differential diagnoses included a mast cell neoplasm or a reactive proliferation of mast cells in the setting of a hematologic disorder consisting primarily of eosinophils. But the mast cell tryptase was negative.

The spindle cells were S-100 positive, however, which he said caused him briefly to ask whether the patient had a “bizarre sort of melanoma.” “[S-100 is positive] basically in all cells derived from neural crest origin, which includes melanocytes and other cells derived from the peripheral nervous system,” he says. So how did he rule out melanoma? “The fact that the eosinophils were the predominant population and the spindle cells only made up a very small population was one clue on the H&E-stained slides alone, but then also the positivity of those spindle cells for CD1a,” he says. “The co-expression of CD1a and S-100 would exclude melanocytes as the cause of that because melanocytes are CD1a negative.”

Dr. Najarian also contemplated other causes like a parasitic infection, he says, “because eosinophils are oftentimes increased within the tissue in response to local parasitic infection.” But the diagnosis was Langerhans cell histocytosis, “proven by immunoreactivity of the focally prominent spindle cells for CD1a and S-100.” Extra-pulmonary multisystem involvement, usually of the lymph nodes, liver, bone, and other sites, is more common in kids but not unheard of in adults, he says. Interestingly, “squashed in the bottom” of the CT chest evaluation was a note that the patient had many lung nodules described as “ground glass change, probably infectious,” Dr. Najarian told attendees. A subsequent biopsy of one of the nodules showed the same process observed in the liver.

“The pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histocytosis is still kind of a mystery,” he says, though the patients are treated with cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. What probably excludes it from being considered by all as a malignancy, he adds, “are spontaneous remissions that can occur in some patients without such treatment, however.”

[hr]

The optimal pre-biopsy laboratory workup

Dr. Robert Najarian says that his institution, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, has a wonderful group of hepatologists who know what constitutes an optimal laboratory workup before a patient moves on to biopsy. But for pathologists who don’t have liver specialists at their hospitals, Dr. Najarian says he would argue that there are minimum requirements in terms of laboratory testing that he’d want to review before making a differential diagnosis and reaching conclusions about a patient’s biopsy. In addition to a basic metabolic panel, the tests include:

- Liver function tests that evaluate acute hepatocellular function (ALT and AST), and markers of bile duct injury (alkaline phosphatase, GGT, and bilirubin).

- Coagulation parameters, platelet count, and albumin to assess the patient’s synthetic function for possible chronic liver disease.

- Viral serologies (HBV, HCV, and others), in addition to autoantibody serologies (antinuclear, anti-smooth muscle, antimitochondrial antibodies, among others) to diagnose specific liver diseases.

Dr. Najarian says iron studies are important, too, including genetic testing for hereditary hemochromatosis in at-risk individuals or those with abnormal iron parameters. “If we are talking about younger patients with chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, studies for copper should be performed as well,” he says. “We know that Wilson’s disease is a cause or contributing factor to liver disease, especially in young patients, that may make them more susceptible to certain exposures to drugs and alcohol.”—Karen Lusky

[hr] CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management