Karen Lusky

April 2018—DCIS or LCIS? Making the distinction can be difficult in some cases. Stuart J. Schnitt, MD, in a session at CAP17 on ancillary testing in breast pathology, delineated the reasons and provided tips, including the role of E-cadherin immunostains to help in this distinction. The cells of DCIS typically show strong membrane staining for E-cadherin while the cells of LCIS are typically E-cadherin negative. But among the tips: If an in situ lesion is E-cadherin positive, it doesn’t automatically mean it’s ductal carcinoma in situ. As he demonstrated in several cases, the lesion could be lobular carcinoma in situ with aberrant E-cadherin immunostaining.

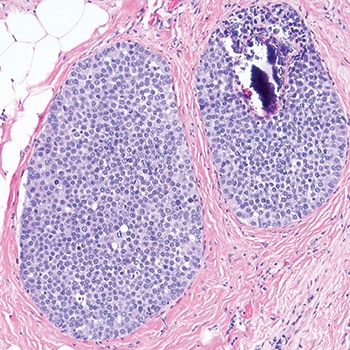

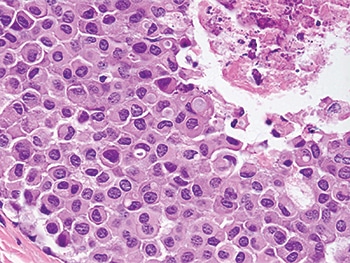

Fig. 1

In the session last fall and in a recent interview, Dr. Schnitt, chief of breast oncologic pathology at Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, explained ways to differentiate LCIS, particularly its variant forms, from DCIS and to detect the aberrant E-cadherin expression seen in LCIS. He and others CAP TODAY interviewed talked about the genomic traits of LCIS variants and the debate about how extensively to treat non-classical LCIS. “One major problem,” he tells cap today, “is there aren’t a lot of data on the subsequent breast cancer risk associated with the variant forms of LCIS.”

Histology is still “the first line of distinction” in differentiating LCIS from DCIS in problematic cases, but in some cases pathologists have to resort to adjunctive immunostains, of which E-cadherin is clearly the “workhorse,” he said. p120 catenin and beta-catenin can be useful in some cases, he illustrated later.

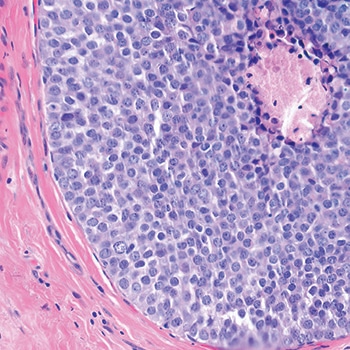

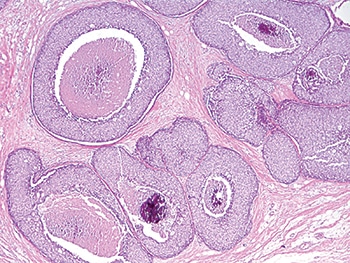

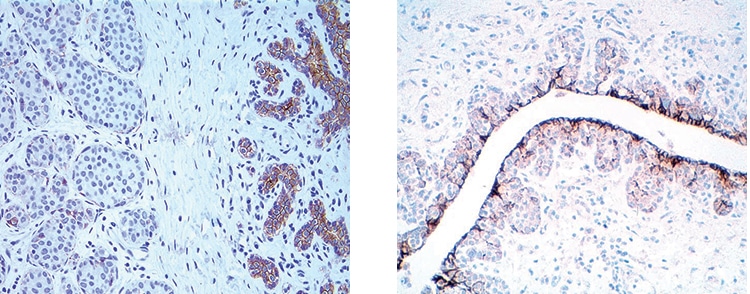

Fig. 2

Dr. Schnitt shared a case in which the screening mammogram of a 47-year-old woman exhibited new microcalcifications. He described an image of the core biopsy as clearly showing “an in situ carcinoma composed of a solid proliferation of relatively small cells with low-to-intermediate grade nuclei.” There is “no evidence of lumen formation, no micropapillations, no cribriforming.” (Fig. 1). At somewhat higher power, there’s “a little area of necrosis and a relatively uniform population of cells,” and perhaps some dyshesion (Fig. 2).

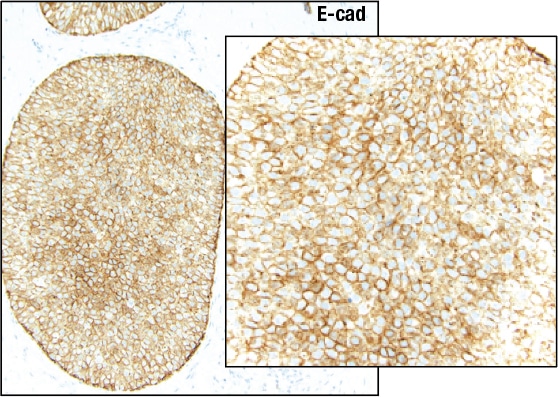

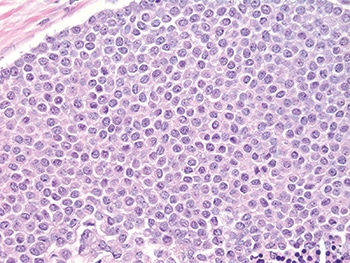

A case like this is “really tough to categorize on H&E alone,” Dr. Schnitt said, so the differential diagnosis was DCIS versus LCIS. He showed an image of the E-cadherin staining (Fig. 3). “One way to view this is to say, ‘Wow, it’s positive; therefore it’s DCIS,’ but quite frankly I think it looks a little funny,” he told the audience. “There is clearly membrane staining, but there seems to be a fair amount of cytoplasmic staining as well, which is not typical for DCIS.”

Fig. 3

Reserving the final diagnosis for the end of his talk, Dr. Schnitt discussed why pathologists might have trouble telling DCIS and LCIS apart. “There clearly is an overlap in the distribution within the ductal-lobular system; DCIS can involve identifiable lobules and LCIS can involve ducts.”

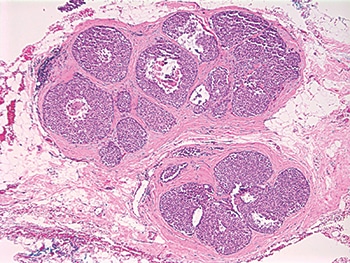

Fig. 4: Pleomorphic LCIS

In addition, some LCIS lesions have features that are more commonly associated in pathologists’ minds with DCIS and vice versa, Dr. Schnitt pointed out. Take, for example, pleomorphic LCIS, which he describes as having considerable variation in cell and nuclear size and shape. It was first reported in 1996 that “you can have this pleomorphic variant of LCIS in association with pleomorphic invasive lobular carcinomas, and then it was found that it can exist as an isolated lesion,” Dr. Schnitt said in an interview. Before 1996, it’s likely these lesions were simply called DCIS.

Dr. Schnitt presented an image of pleomorphic LCIS, predicting that “any reasonable pathologist” viewing something like it at low power would say the lesion looks like it’s probably DCIS (Fig. 4). He pointed to a solid proliferation of very atypical cells in the various spaces with areas of comedo necrosis and calcifications and, at higher power, “marked nuclear pleomorphism” (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Pleomorphic LCIS

He shared an example of LCIS with necrosis. “And again, I think any reasonable pathologist would first look at this and say, ‘Well, it looks like DCIS’ because it does look like DCIS—solid proliferation, areas of comedo necrosis, and calcifications—but at a higher power the cells look more lobular than ductal,” he said (Figs. 6 and 7).

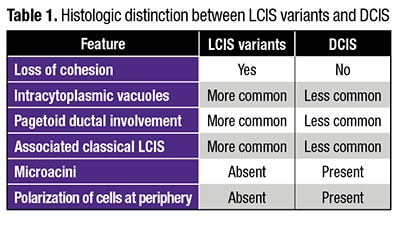

Intracytoplasmic vacuoles, pagetoid ductal involvement, and loss of cellular cohesion should all make pathologists think of an LCIS variant instead of DCIS, Dr. Schnitt said, presenting a table summarizing the histologic features he views as most useful in distinguishing between LCIS variants and DCIS (Table 1). Dyshesion is a useful clue that the lesion is LCIS rather than DCIS, he says. “One of the characteristic features of LCIS is that the cells don’t stick together very well because they typically lose E-cadherin, which is a cell adhesion molecule,” he says. Although that’s one of the characteristic features of LCIS, including the variant forms, it’s not always observed, Dr. Schnitt adds, noting that he’s seen more cohesive lesions that are LCIS.

Fig. 6: LCIS with necrosis

“Certainly, in the guilt-by-association category,” if there’s associated classical LCIS, “you should be thinking that perhaps this is more likely a lobular variant than DCIS,” he said. “Conversely, if you see cells polarizing around microacini and polarization of cells at the periphery of the involved spaces, you should start thinking more ductal than lobular carcinoma in situ.” Sometimes it’s impossible on H&E sections alone for pathologists to know for sure if they are dealing with DCIS or LCIS, he added, in which case immunostains are used.

“Loss of E-cadherin expression is arguably the defining feature of LCIS and invasive lobular carcinoma,” Dr. Schnitt said. “E-cadherin molecules are involved in homodimerization on adjacent cells, which holds the cells together.” The intracellular domain of the E-cadherin molecule is connected to the actin cytoskeleton by a variety of catenins, including beta-catenin and p120 catenin, he said. Together, these catenins and E-cadherin make up what has been referred to as the “cadherin-catenin complex.”

Fig. 7: LCIS with necrosis

Many of the cases showing loss of E-cadherin expression have loss of heterozygosity at the site of the E-cadherin gene at 16q22. “This is often accompanied by inactivating mutations or promoter methylation of CDH1,” he said. Other mechanisms may also result in E-cadherin loss, “but whatever the combination of events, it results in biallelic silencing of the gene and loss of protein expression.”

Dr. Schnitt presented an example of LCIS involving a lobule that he noted has total loss of E-cadherin expression (Fig. 8). The uninvolved lobule on the right side of the left image shows membrane expression in the epithelial cells. In the image on the right, he pointed out “pagetoid involvement in the duct by LCIS. The LCIS cells are negative. The residual epithelial cells are positive.”

“In contrast, DCIS is typically E-cadherin positive with strong membrane staining for E-cadherin,” Dr. Schnitt said. Whether it’s low-grade cribriform or a high-grade comedo, “DCIS is virtually always E-cadherin positive.” (Fig. 9).

“In contrast, DCIS is typically E-cadherin positive with strong membrane staining for E-cadherin,” Dr. Schnitt said. Whether it’s low-grade cribriform or a high-grade comedo, “DCIS is virtually always E-cadherin positive.” (Fig. 9).

In a separate CAP17 presentation on high-risk breast lesions in core biopsies, Sandra J. Shin, MD, professor and chair, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Albany Medical College, reported that she uses E-cadherin all of the time. “It’s very helpful when you are trying to decide between LCIS or DCIS,” she said, “especially when you are thinking it may be DCIS extending into adjacent lobules, and there’s loss of E-cadherin expression indicative of LCIS or ALH [atypical lobular hyperplasia].”

Dr. Schnitt said he thinks it’s probably safe to say that loss of E-cadherin expression by immunohistochemistry is characteristic of LCIS, but the converse is not necessarily true. “That is, the presence of E-cadherin expression does not preclude a diagnosis of LCIS in the context of the appropriate histologic features.”

Fig. 8: LCIS: Loss of E-cadherin expression

Many pathologists are inclined to look at E-cadherin staining in a binary way, he says. If the lesion is positive, they call it ductal; if it’s negative, the lesion is considered to be lobular. “But we know that you can get aberrant E-cadherin expression in LCIS cells,” he says. “We also know that normal ductal epithelial cells or myoepithelial cells that are admixed with the LCIS cells are E-cadherin positive, and those cells can be misconstrued as the LCIS cells themselves staining for E-cadherin.”

He presented an example of LCIS involving a duct with preexisting usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH) (Fig. 10). “If you do an E-cadherin stain on this, you find that the UDH is positive, the LCIS cells are negative, but if you don’t recognize morphologically that this is UDH, you might say some of the neoplastic cells are E-cadherin positive; therefore, this might be interpreted as DCIS or mixed DCIS and LCIS,” he said.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management