Andrew S. Field, FRCPA, FIAC, DipCytopath(RCPA)

January 2018—In countries with developed medical infrastructure, the use of breast fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) cytology has had its share of challenges over the past 20 years, among them the use of core needle biopsies. In developing countries where the use of FNAB cytology has been increasing rapidly, breast lesions are one of the most common sites sampled by FNAB. In 2016, the International Academy of Cytology Executive Council put together a “Breast Group,” which consists of cytopathologists, surgical pathologists, radiologists, surgeons, and oncologists working in breast care, with the aim of producing a comprehensive and standardized approach to breast FNAB cytology reporting.1,2

This approach will address the current challenges to FNAB cytology and include best-practice guidelines for the indications for breast FNAB cytology and the techniques of FNAB, smear making, and material handling. It will include a practical, standardized reporting system, including report content requirements, with defined descriptive terms and categories, structured reports with checklists and formats, and recommendations for the use of ancillary diagnostic and prognostic tests and suggested management algorithms. A standardized approach with best-practice guidelines will improve FNAB and smear-making technique, training, routine reporting, and quality assurance programs. If linked to management recommendations, it will improve clinicians’ understanding and use of FNAB cytology services.

Why a new reporting system?

Since the 1996 National Cancer Institute consensus meeting made recommendations for breast FNAB cytology reporting, there have been many developments in the diagnostic workup of breast lesions in surgeons’ rooms, breast clinics, and mammographic screening program assessment clinics, including the use of tomographic mammography, ultrasound, and MRI.3 There have also been significant developments in the role of various diagnostic procedures in management algorithms, and the use of breast FNAB cytology now varies greatly between breast clinics for symptomatic women, mammographic screening program assessment clinics, and hospitals in various cities and states as well as between developed and developing countries.

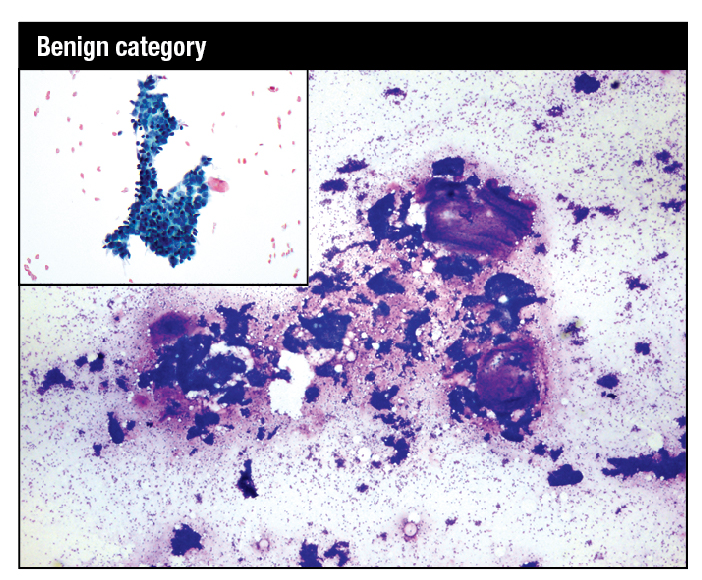

Modified Giemsa stain. Highly cellular smear showing fibroadenoma with mix of small and large hyperplastic ductal epithelial cell tissue fragments and large myxoid stromal fragments. High-power image shows myoepithelial nuclei on the epithelial fragments and in the background as bare bipolar nuclei. Inset: Modified Giemsa. Fragment of benign breast tissue consisting of ductal epithelial cells with interspersed myoepithelial cells.

Breast FNAB cytology does offer many advantages because it is quick, is minimally invasive, causes minimal physical and psychological discomfort, and is acceptable to patients. It is a relatively inexpensive test. It enables rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE) and provisional reporting, which is ideal for multidisciplinary “one stop” diagnostic clinics that provide same-day clinical, radiological, and provisional cytological assessment.

Breast FNAB is a highly specific and sensitive test to accurately diagnose benign and malignant lesions when undertaken by an operator experienced in the biopsy technique and cytopathologists experienced in reporting breast cytology. It is cost-effective for the preoperative diagnosis of palpable and ultrasound-detected impalpable breast lesions. It can also provide formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded cell blocks for immunohistochemistry for prognostic indicators, including estrogen and progesterone receptors and for in situ hybridization for HER2. Material from directly smeared slides or cell block material can be used for PCR and other potential molecular testing.4

In medically under-resourced developing countries, where more than 80 percent of the world’s population lives, breast FNAB is the test for all palpable lesions, in a setting where preoperative imaging and core needle biopsy and histopathology are not readily available and are expensive options.5,6

Challenges and solutions

The greatest challenge now to breast FNAB cytology is the quality of the FNAB procedure and of the smearing technique. These are crucial to a successful breast cytology service and the major source of quality assurance problems with breast FNAB. Poor performance of the FNAB and the direct smear are the elephant in the room in any discussion of the role of breast cytology.2

Currently, radiologists and their trainees perform the majority of breast FNAB in the developed world, rather than cytopathologists. There is a long and successful tradition of cytopathologists carrying out FNAB of breast palpable lesions. Cytopathologists are immediately aware of the quality of their technique because they are reporting the slides, while radiologists often have minimal contact with the reporting pathologist. FNAB is regarded as a simple test, but it requires good training and ongoing experience with constant monitoring of the diagnostic yield and adequacy rates. The number of FNAB of breast has decreased in the developed world, resulting in fewer training opportunities for trainee radiologists and pathologists and a lack of adequate training. This has led to a general decrease in the quality of breast cytology specimens.

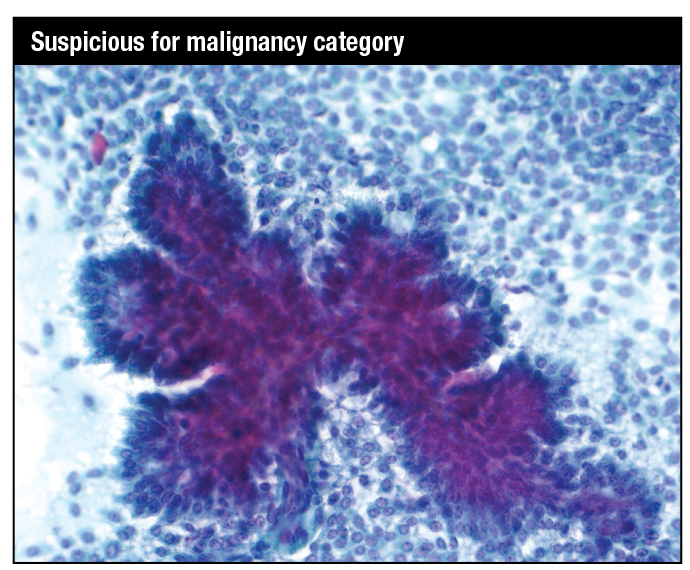

Papanicolaou stain. Papillary tissue fragment with fibrovascular core covered in multilayered atypical cuboidal to columnar epithelium with moderately pleomorphic nuclei in a background of dispersed single cells showing moderate nuclear atypia: specifically, suspicious for papillary intraduct carcinoma, with or without an invasive component.

The radiologist uses ultrasound guidance for palpable and impalpable lesions, which has increased the range of accessible lesions but at the same time accentuated the problems in the performance of the FNAB and in making smears. The key elements in a breast FNAB are the fixation of the specimen and a rapid technique. Ideally, the needle should be introduced for fewer than 10 seconds, with 10 to 15 rapid passages of the needle into and just through the lesion, using the cutting action of the needle bevel. For cytopathologists and radiologists, ultrasound can be helpful in assessing palpable lesions. But it is more difficult to fix a palpable breast lesion when an ultrasound probe is present, and the time the needle is in the lesion, the “dwell time,” is lengthened, leading to an increased incidence of blood contamination and clotting of the material in the needle. Further, if aspiration is applied early in the FNAB without the cutting action of the needle having been utilized, the result may be inadequate, hemodiluted, and obscured material.

The second crucial preanalytical step is preparing direct smears, and poorly trained operators or their assistants can ruin good material by using poor smear-making technique. Liquid-based preparations do avoid poor smearing technique and the air drying of alcohol-fixed material, but they prevent ROSE, decrease the crucial pattern recognition diagnostic features in breast cytology, and increase expense.

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management

CAP TODAY Pathology/Laboratory Medicine/Laboratory Management